Toyin Ojih Odytola: To Wander Determined THE WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART

By Olivia McCall

Vibrant shades of color stand out against serene lavender walls, but what ultimately draws one into each individual frame is the lush narrative so beautifully conveyed. This pastel hue indicates that, as the viewer, you have entered her story – it exists there in that space, to be experienced and apprehended. This is the space of To Wander Determined, a solo exhibition by Nigerian-born artist Toyin Ojih Odutola, boasting a title that immediately establishes a contradiction. How may the aimless action of wandering be executed determinedly, purposefully? It seems this quality of determination is found in the visages of the sophisticated figures portrayed from canvas to canvas, effusing this power of intent.

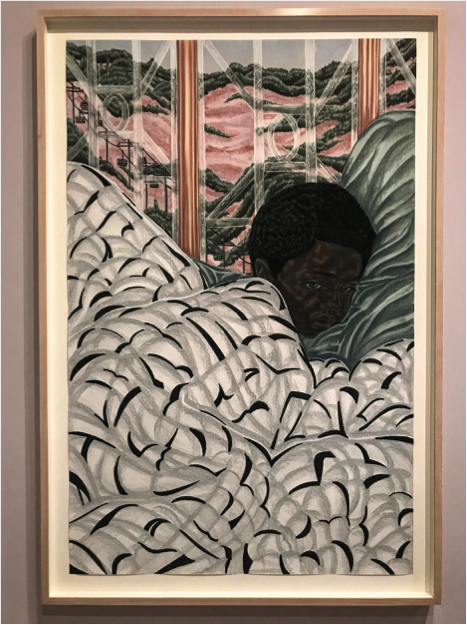

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Unfinished Commission of the Late Baroness, 2017

The delicate interplay of light and shadow enhances the ethereal quality that somehow remains much so rooted in reality. An earthly radiance and luminosity is woven into an intricate, somewhat unspoken narrative; however, while this story may be largely silent, it holds its weight through implications. Each canvas has a delicate, brushed texture – a texture that does not discriminate between foliage, object, scenery, or even skin. The material, tangible quality of the skin surface is inescapable; it is at the core of each vignette. This is a detail that Ojih Odutola clearly wishes to bring attention to, referring to the skin as this “impenetrable mark that I am expanding and making more nebulous, less static, less monolithic.” It is a concept that has been omnipresent in her work, and is clearly apparent in To Wander Determined. Here, the skin is not flat, is not lifeless, but dynamic and variable. It infuses each figure with vitality, and it enhances the luxurious quality of life that is elegantly rendered.

Both interior and exterior spaces are conveyed through delicate texture, which adds gravity to each image through visualizing the hand of the artist. “First Night at Boarding School” presents a combination of shades, though they are subtle alone. An emotive, young face cloaked in a white, flowing cloth accented with black details establishes a sense of distress existing in a separate realm. Identity is never confirmed, neither in person nor in place. In “Unfinished Commission of the Late Baroness,” identity is a topic to be questioned once again – the only bodily aspect entirely complete is the visage. She descends into sketched lines and fluctuations between light and shadow, ultimately approaching a materiality quite disparate from that which is established through the skin. Here, this materiality is more literal, no longer posed as a question or as an added weight to identity, but illustrated as a reality.

Toyin Ojih Odutola, First Night at Boarding School, 2017

Before only placing her figures in decontextualized spaces, the move into a space of narrative is a recent one for Ojih Odutola. Through narrative, she wishes to present figures in a way that evokes the sense of this has always been. There’s a degree of elusiveness that she maintains as well, keeping distance from capturing individual identity, and instead creating figures on the canvas that could be anybody, could resonate with any identity. Within this small gallery on the ground floor of the Whitney, there rests the concept of an aristocracy of a certain kind – these are figures who do not question their place, their status. They do, however, seem to question the viewer; all of the eyes give the impression of gazing past the confines of the canvas. The viewer is not necessarily being confronted, but they are not anonymous, either; they are noticed.

1 Ojih Odutola, Toyin. To Wander Determined. Oct. 20 2017 — Feb. 25 2018, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

2 Ojih Odutola, Toyin and Mary Sibande, moderated by Kellie Jones. “Art & Equity.” Barnard College, 31 January 2018, New York, NY.

Georgia O’Keeffe: Feminist by Nature

By Cassidy Hall

Last June, I journeyed from my Harlem apartment to the Brooklyn Museum for the greatly anticipated exhibition Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern. In the winding galleries, I not only found the unapologetic feminist art I had come to see, but also an earnest portrayal of the human experience; I learned from her strength and from her surprising sensitivity. Georgia O’Keeffe, a woman who transformed American modern art, challenged gender norms, and quite literally wore her pride on her sleeve, changed how I define feminism.

The simplicity of O’Keeffe’s paintings is striking. Each of her pieces makes a subtle statement. A flower, no matter how grand, is still a flower. Many audiences, including her late husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, claimed her flowers are comparable to female genitalia, metaphors for blossoming sexuality, or overwrought feminist statements. O’Keeffe rejected these observations, retorting that viewers only see what they want to see out of art: “you hung all your associations with flowers on my flower… as if I think and see what you think and see—and I don't.” Rather, O’Keeffe was drawn to flowers for their common beauty. She sought to eliminate any distractions from the subject of her paintings, emphasizing instead simplicity and form.

The minimalism of canvases covered entirely by singular, bold blossoms is translated into her later work, especially her paintings of skyscrapers. O’Keeffe’s illustrations of New York are not as busy or as crowded as many of her predecessors’ portrayals of the city. Instead, she intensifies the nobility of the craning buildings. Staying true to her fondness of striking color and clearly defined shapes, O’Keeffe eliminates all excess from the cityscapes, allowing the architecture to be the centerpiece. Seeing city life portrayed in such a raw form, I was overcome by hope and loneliness. My insecurities were drawn to the surface by the authenticity and simplicity of the statement. Beholding nothing but the angular, monochromatic skyscrapers, one begins to impose one’s own experiences onto the artwork. Perhaps this is why so many critics pass judgments about the underlying meaning of O’Keeffe’s statements: O’Keeffe begs her audience to realize their personal emotions in art.

The most poignant display in the exhibition was a series of photographs of O’Keeffe. The portraits demonstrate that O’Keeffe’s art is inseparable from her character. She often stands like a western cowboy, ruthless and present, demanding the camera to capture the angles of her body: the sharp incline of her chin, the daring expression of her eyes, and her strong, yet graceful disposition. Her taste in fashion is a reflection of her demanding presence. She plays with gender neutrality in clothing, sourcing inspiration from her environment. Whether wearing button-up blouses, cowboy hats, or trench coats, O’Keeffe presented herself with tactful, consistent care. She gravitated towards clothes that reflected her artwork: three white blouses hung proudly and delicately in a row at the museum, curated to mirror her paintings of flowers. With no attachment to either gender, the androgynous wardrobe bears a neutral and unassuming beauty.

Much like her paintings, O'Keeffe’s style is inspired by her environment and its natural resources. She immersed herself in her surroundings and like a hawk circling the western prairies never went unnoticed. In New Mexico, O’Keeffe redefined herself, fusing her art, habitat, style, and character into one identity. Contrasting to her nostalgic cityscapes, O’Keeffe’s renderings of the American southwest exude majesty and incite curiosity. Amid joy and color, O’Keeffe paints skulls, carcasses, and empty space. The contrast functions as a memento mori, expressing human suffering and existential doubt in physical form. She creates an intricately shaded world where life and death are equals, gender is as fluid as changing outfits, and flowers and skyscrapers alike are iconic. Embodying her aesthetic philosophies in both her art and identity, O’Keeffe was not a feminist by choice but a feminist by nature. Her art is influential not only because it serves to empower women, but also because it exposes the universal need for free self-expression. Indeed, O’Keeffe’s legacy is proof that feminism is innate in all of us.