Marie Aimee Fattouche

Marie Aimee Fattouche is a French and Middle Eastern visual artist living and working in London. Before completing her MA in Fine Arts at Chelsea College, she worked in and around the arts, painting, designing, and curating in Paris and Marrakech. This summer, she invited The Margin to her studio, a converted industrial space situated under the railway arches of the London tube. As trains moved overhead at regular intervals, we sat down to tea among stacks of antique books. The long and narrow rooms, occupied by fellow local artists, are filled with mannequins, mirrors, props, and other oddities.

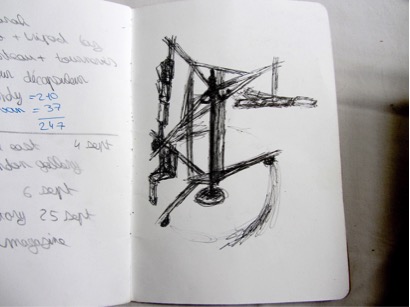

At the time, Fattouche was in the final stages of constructing her most recent work, a sculpture in aluminum titled Metro boulot dodo. The structure, with metal appendages that can be moved like a revolving door, is a statement on the rigidity and physical strain of urban life. A week later, in a group exhibition she curated, Fattouche performed with her work to exhibit a body in motion with the metal. The Margin caught up with Fattouche the day before she left for the Red Gate Residency in Beijing, China, where she is now living for a month. We spoke to her about her creative process and the recent exhibition of Metro boulot dodo.

Metro boulot dodo

TM: How was the exhibition?

MA: Good vibes, good people came. I was surprised. For this show, I didn’t have many expectations and loads of people came. We dragged the party out until one in the morning!

TM: Did the audience interact with the sculpture?

MA: Some people did. I improvised a short performance. I thought I would do more movement with the sculpture but I did it for less than an hour. I wanted to enjoy the evening. When I was showing the piece to friends, we would experiment and improvise with it.

Fattouche performs with her sculpture.

TM: How did the exhibition come together? Did you organize it yourself?

MA: For this exhibition, a friend of mine with a gallery contact gave me three days in the space. I didn’t know what I wanted to do at first, and I thought maybe I would do a solo exhibition. But then I realized I wanted to curate a full show, so I chose the artists, myself included.

TM: Was this the first time you have curated a show?

MA: No, but it was the first time in a while. When I was working at the gallery in Morocco, I helped to curate some of the shows. It has been two years since then. It’s also very different to curate a show you are exhibiting in.

TM: The other work shapes your own.

MA: Yes, definitely. I brought a lot of diversity into the show. There was a sound piece, a performance, sculpture, installation, and painting.

TM: Can you tell us how your sculpture came to be? Can you describe what it looks like?

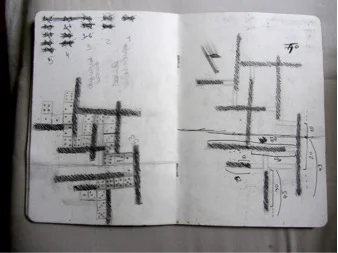

MA: My piece is called Metro boulot dodo. It’s a French expression that means “Tube work sleep.” I wanted to show the routine of urban life and what it does to our physicality. There are three positions of your body. You are not allowed to live outside of these three positions any more. You can only stand up, sit, or lay down. I thought, okay, what do I feel from this physicality? I feel quite constrained by it. Today, I have a more fluid life, as I am only focusing on my art. I feel less constrained in routine. But before, I was working in routine for six years. Your alarm goes off, you work, you go. It became normal to be tired. This environment made me feel like a puppet. The movement of the sculpture is like a puppet on strings—up, sit, down, up, sit, down, up, sit, down. I started drawing lines in those directions—up, sit, and down. When you write it on paper, these three signs repeated again and again look like a coded language, like Morse code.

TM: You began the sculpture by annotating movements of the body. Do you always start with sketching? How do you prepare for the first moment with your materials?

MA: All my ideas come from a concept. First, there is a lot of research, thinking, writing, and sketching. When I have an idea, I don’t necessarily know what I want it to look like. For Metro boulot dodo, I knew I wanted to work with the idea of dominoes—dominoes being analogous to humans. In the previous works I made with this idea, the pieces of the sculpture formed a strong architecture, interacting with each other socially. But in this new sculpture, I wanted to explore the form of dominoes. They are being pulled by a string and tortured by this type of movement. I start small. I start with the character of the sculpture, then I work on the context.

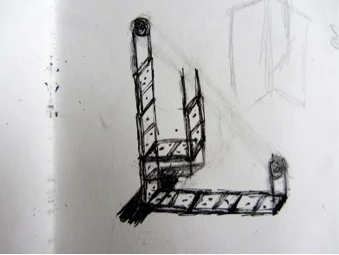

Early sketches of dominoes

TM: Why do you use the idea of dominoes? How do dominoes relate to humans?

MA: Many artists have worked with dominoes because they can express consequential movement. If you put them side by side and one falls, it exerts a certain amount of physical force on the whole group. The consequence, the fate interests me. I am also interested in the duality of dominoes and how they are built with differently numbered halves. My work is about understanding duality in general. Duality is not a new subject, but I try to understand it in my own life. Why do I have some moments when I am depressed and why do I have some moments when I feel very high on life? Why is there good and evil? How can they be associated?

TM: Are you going to continue to use dominoes as a theme when you go to Beijing, or are you going to do something completely new? Do you know?

MA: I have no idea. Dominoes are Chinese originally. And I had no idea that I would be going to China when I started working with dominoes.

Domino details in aluminum

TM: A lot of your ideas are very universal, broad concepts encompassing humanity and existence. Are you influenced by the different places you’ve lived, and the different cultures you know?

MA: I guess that I am. I have never really thought about it like that. It’s true that I choose to talk about universal themes because in the end, making art is about trying to understand yourself. In any art form, the artist is trying to understand their inner-self and their surroundings.

TM: Your earlier work was about context and content. But now that you work focused on form, what you have removed is accentuated.

MA: Yes. That is the point of it. The pieces of the sculpture exist in form but the context in which they exist has disappeared. There is deconstruction of movement in my sculpture. I realized only yesterday that I see movement by decomposing it. And I think that comes from seeing digital images. When you try to capture movement digitally, it becomes blurry. In blurriness, the content and context are lost. You can only feel the movement. I am starting to think more of my work as digital. And I am starting to think how the digital world has influenced my work. I am not very conscious of it yet. But it’s there.