Issue No. 2

Table of Contents

A Note from The Margin

Drawings // Concreto Tótem by Nikita Garrido

Feature Lani Dickinson

Photographies de la lumière et du corps by Maéva Lecoq

"When the Moon Covers Up the Sun" and "St. Louis Bound" by Megg Farrell

Toyin Ojih Odutola: To Wander Determined by Olivia McCall

Work Out: Exercise Guide for Sedentary Girls by Charlotte Barnett

Antigone // Ismene by Elinor Hitt

From The Margin

Dear Friends,

Why do we tell stories? Stories, shaped by the silences from which they emerge, let us make sense of our thoughts, our sympathies, and our rage. Stories let us find, as Mary Oliver says, our “place in the family of things.” In THE MARGIN, ISSUE NO. 2, many different stories are told in many different ways—through making music, starting dialogues, and moving our bodies.

Our feature for this issue is San Francisco-based dancer Lani Dickinson, who is breaking boundaries and rewriting the language of dance by exploring how the body can be used to tell new and often unheard stories. I would like to thank all our contributors, editorial staff, and readers. Without a community, stories cannot be told or heard.

Gratefully yours,

Elinor Hitt

Editor in chief

THE MARGIN MAGAZINE

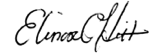

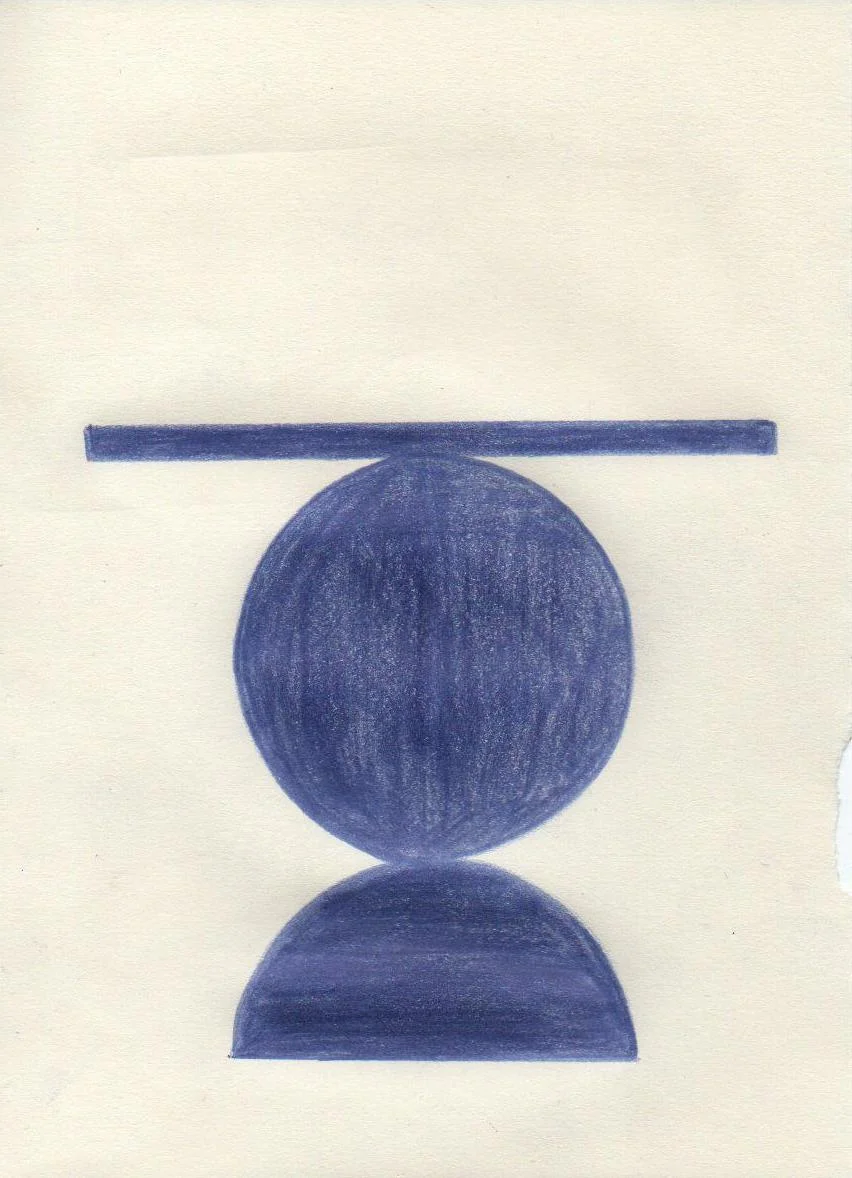

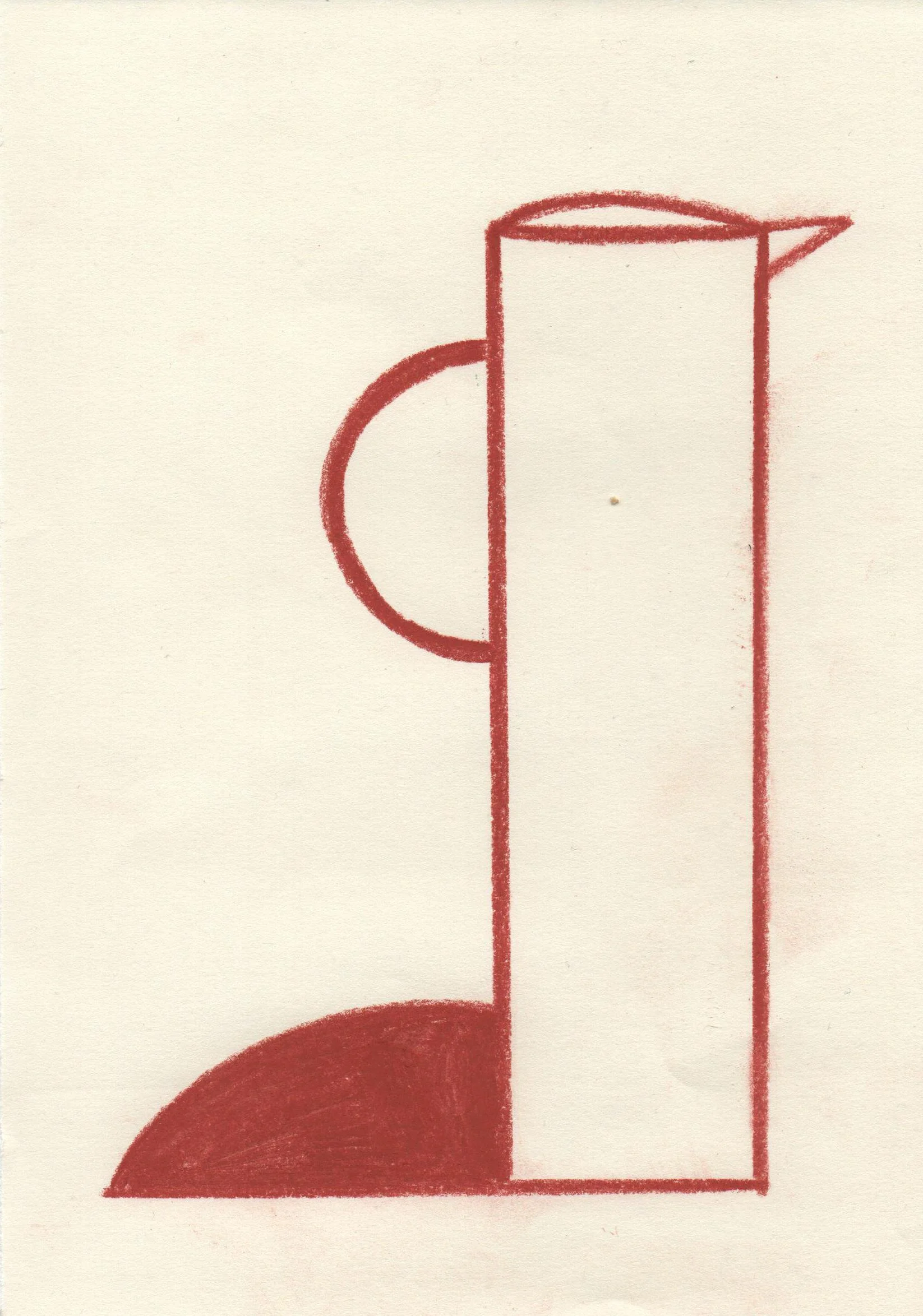

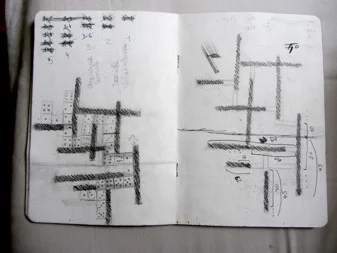

Drawings // Concreto Tótem by Nikita Garrido

https://www.coolmachine.fr/shop/lampe-concreto-totem/

Concreto Tótem is a concrete lamp topped by a glass lampshade. The lamp has been hand-crafted in a workshop based in Versailles and each glass piece is made from old flasks. Each lamp is unique and made to order.

Lani Dickinson

Photo by: Rob Kunkle / Good Lux Photography

Lani Dickinson is a dancer in San Francisco, California. After training in classical ballet, she graduated summa cum laude from the LINES Ballet BFA program in collaboration with Dominican University of California where she was first exposed to contemporary dance. In 2015, Dickinson received the Princess Grace Award. She now dances with AXIS Dance Company, a physically integrated contemporary company in Oakland, California. We spoke to Dickinson in January about her training, her current projects, and her work translating the language of dance to fit all bodies.

The Margin : Are you coming from rehearsal?

Lani Dickinson: I had a rehearsal earlier today and I also stayed to work on a solo.

TM: What’s it for?

LD: There is a festival at the Grace Cathedral up on Nob Hill in San Francisco. This year there are two hundred artists performing. I’m one of them. There are different stations throughout the space with some dance groups and some soloists. You perform in a loop through the night. It’s really amazing. Last year, I did it with AXIS.

TM: So the audience walks through?

LD: Yes. There’s a great rotunda in the center. That’s where I danced last time. This year, I’m dancing in a little ten-by-ten space in the back. It's right where this red cube is [located] which is considered to be the Grace Cathedral’s heart. They say if you picked up the building and put it on its back, that’s where the heart would be.

TM: That’s beautiful. Do you know the other performers?

LD: Most of them that I know went to the same college I went to—the [Alonzo King] LINES BFA program.

TM: That’s why you moved to San Francisco—to do the BFA program?

LD: Yes. Then I went right into dancing with AXIS Dance Company three months after graduation and I’ve been with them for about a year and a half.

TM: Is it mostly contemporary dance?

LD: It’s a contemporary repertoire dance company [composed] of people with and without physical disabilities. We do a lot of creative movement because it’s a physically integrated dance company. Currently we have three dancers that are not disabled and three that are disabled.

TM: Do you also do improvisation?

LD: A big part of the movement we do is self-generated and often created from improvisation tasks. What we teach and how we communicate revolves around having an awareness of the language we use. So instead of saying “your legs,” you say “the lower part of your body,” or “upper part of your body” for your arms. Or we use terms like “spiral”—a lot of imagery. It seems like a simple concept, but it is about breaking habits and about being aware of what kind of language you use. Because language is a very serious barrier. We do summer intensives at AXIS and people come from all over the world. There are usually a couple people who get emotional because they think “I never thought I could take ballet.” If you look at ballet terminology, they say “plie” is “two legs bending.” Or “port de bra” is literally “carriage of the arms.” It’s very body part specific. Our new artistic director, Marc Brew, was a ballet dancer before becoming disabled. He’s now using a chair because of a car accident. We’ve worked a lot on how to translate ballet. He does it with his arms mostly. A challenge for him is to keep that new language consistent—he’s not just making it up as he goes. A tendu for him is always the same thing with his arm.

Photo by: Kyle Adler / www.kadlerphotography.com

TM: Do you think you would ever want to teach?

LD: I love teaching. We teach a lot. We have three pillars of activity in our company mission: artistry, education, and advocacy. We perform, but when we tour, we often go to colleges and spend up to a week with their dance majors or even with their physical therapy majors. We exemplify the social model of disability. Also, when we get the opportunity to teach kids ranging from 2nd grade to 8th grade, I enjoy that too. Just because I am the teacher does not mean that I am not learning. That is what I find beautiful.

TM: Would you ever want to choreograph?

LD: I choreographed in my senior year of high school and in my senior year of college. And right now I’m choreographing my own solo. I do like choreographing. I think it brings out a lot of things about me that I can discover through movement.

TM: Do you prefer being the dancer or the creator?

LD: I prefer being the dancer. Lately, a lot of the choreographers whom I’ve worked with inside and outside AXIS ask us, the dancer, to create movement phrases prompted by a concept or quality. But I do like learning a phrase and then putting my own spin on it. Or problem solving through it. So really the dancer and the creator are the same thing to me.

TM: At AXIS, do they bring in other choreographers or are you mainly working with the director?

LD: We bring in other choreographers. Marc, he set a piece on us. We also have a piece by Amy Seiwert, who is a well-known Bay Area choreographer. And now we are working with Nadia [Adame]. She, too, was involved in a car accident. She’s disabled. She uses a cane. We work with both disabled and non-disabled choreographers. AXIS is physically integrated but we are working on getting the company just plain-and-simple integrated. We have a very diverse group. James Bowen, who I dance with really well, is a black man. He speaks a lot about he danced for a company of black [dancers]. He started dancing because he wanted to learn to twerk! He also trained in professional cheerleading. Integrated dance was something new to him as it was for me too. We were hired at the same time. He feels as strongly as I do about the diversity of a team being a positive reflection of a company’s mission. Despite differences in bodies, cultures, or dance training we are able to move together. Dancing with a person using a wheelchair is different. But with conversation, any partnership is possible—it just takes practice. I’ve really gotten to know my fellow dancers and choreographers in this inclusive setting. It’s a two-way thing, opening up. I’m not saying disabled people have the best stories. Not at all. But people with different backgrounds—different race, different sexuality—have certain stories that they can tell or express through dance. It’s amazing when you can see where the stories intersect. That’s when you can find common ground.

Photo by: Dino Corti

TM: How was it switching from ballet training to contemporary dance?

LD: It was hard. I wasn’t ready to let go of the rigor of ballet—the routine of it all. But I don’t miss the exclusivity of it. In ballet, you get stuck in your own world. At least I did. Getting into AXIS and contemporary work, I started to find my own voice within the bigger world.

TM: When did you start branching out? Was it at AXIS? Or was it during LINES’ BFA?

LD: That’s a good question. I branched out during LINES BFA because it came before AXIS. I think in dance we are constantly making breakthroughs, gaining confidence, and experiencing new styles as they come. I branched out the time I took ballet at eight years old. I branched out when I spent my first month away from home, on my own, to attend the Boston Ballet Summer Program. I grew from my experience attending Idyllwild Arts Academy in California. Each and every environment has exposed me to new things. I learn about dance, I learn about life. More recently, AXIS has helped me branch out in being comfortable in the body that I was born in.

TM: What do you like about living in San Francisco?

LD: I love hiking.

TM: Where do you hike?

LD: North of here is Mount Tamalpais. Point Reyes. Stinson beach. You can take a hike from Mount Tam all the way down to the beach. There’s Muir Woods. South, there’s Big Sur. One hike I went on the other day is in San Pedro. There’s a lot. That’s what I like about San Francisco. For the weekend, you can drive and be somewhere else.

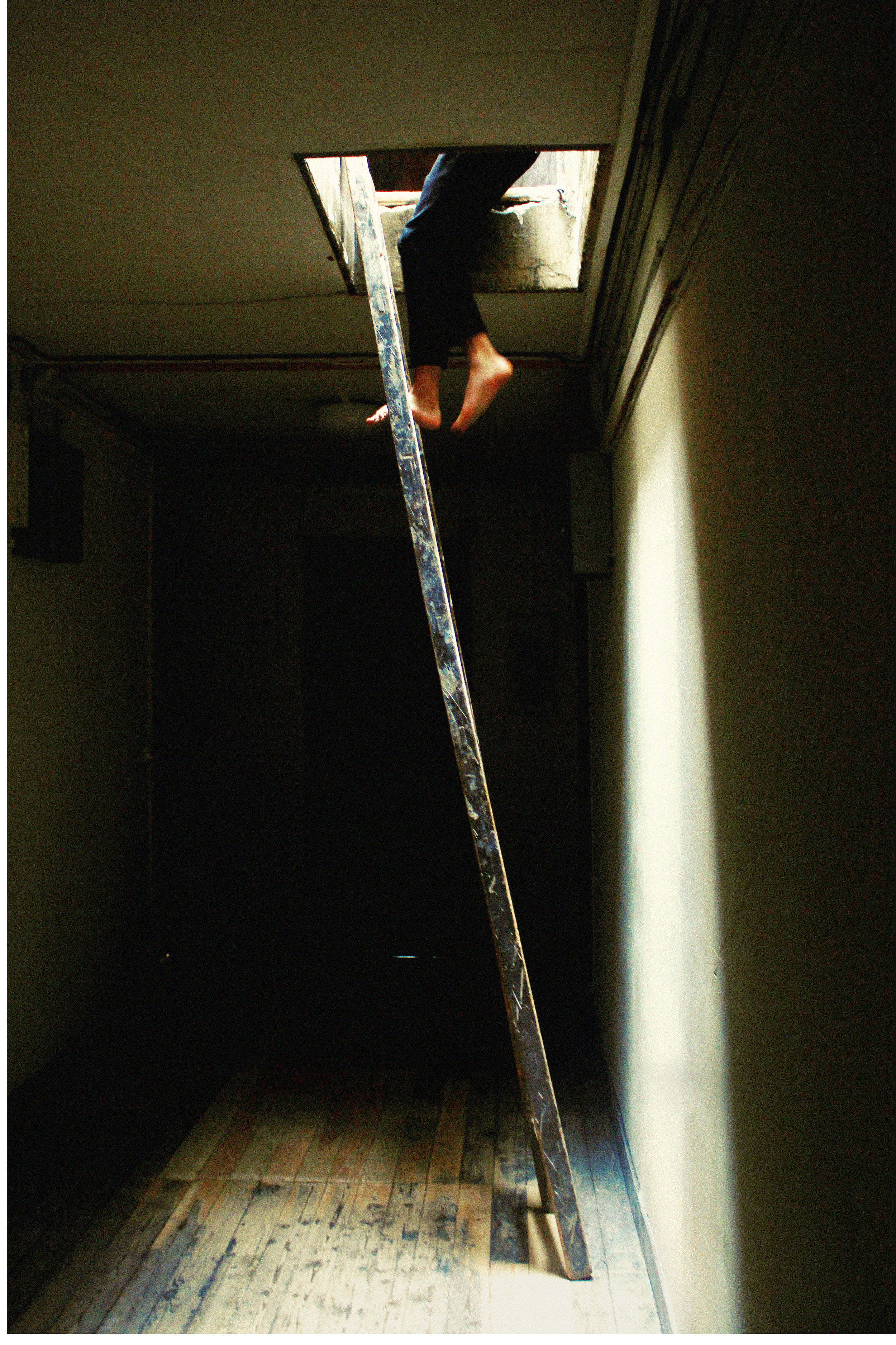

Photographies by Maéva Lecoq

"When the Moon Covers Up the Sun" and "St. Louis Bound" by Megg Farrell

Megg Farrell grew up in an artistic household. Her mother was an actress and playwright and her father was an actor and songwriter. She was encouraged to express herself through her art at a young age and began performing her original music in the East Village by the age of 16. After high school, she spent time living in Tennessee. In college she started a group, The Whiskey Social, a folk group full of singing and drums. They toured along the East coast until she moved to Paris to study jazz. In Paris, she formed a new Whiskey Social and joined the expats who would busk along the Seine. As she studied jazz, she continued writing and performing folk.

She began performing in the New York jazz scene out of college and was swallowed up by it. She began gigging in the old-time jazz and gypsy jazz scene and her career took off. She has been performing full-time under the name Sweet Megg and has built followings in New York, Asheville, Nashville, and St. Louis.

Now, Megg has decided to get back in touch with her songwriting roots. She has begun writing original jazz songs for Sweet Megg and has also formed a new project Megg Farrell & Friends. With Megg Farrell & Friends she is performing her original folk tunes as well as rowdy burning country tunes à la her heroes Emmylou Harris & Dolly Parton.

Megg has two albums out on iTunes and Spotify. You can listen to her jazz music on the album Sweet Megg & the Wayfarers and her original music on Fear Nothing by Megg Farrell.

Toyin Ojih Odytola: To Wander Determined

THE WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART

By Olivia McCall

Vibrant shades of color stand out against serene lavender walls, but what ultimately draws one into each individual frame is the lush narrative so beautifully conveyed. This pastel hue indicates that, as the viewer, you have entered her story – it exists there in that space, to be experienced and apprehended. This is the space of To Wander Determined, a solo exhibition by Nigerian-born artist Toyin Ojih Odutola, boasting a title that immediately establishes a contradiction. How may the aimless action of wandering be executed determinedly, purposefully? It seems this quality of determination is found in the visages of the sophisticated figures portrayed from canvas to canvas, effusing this power of intent.

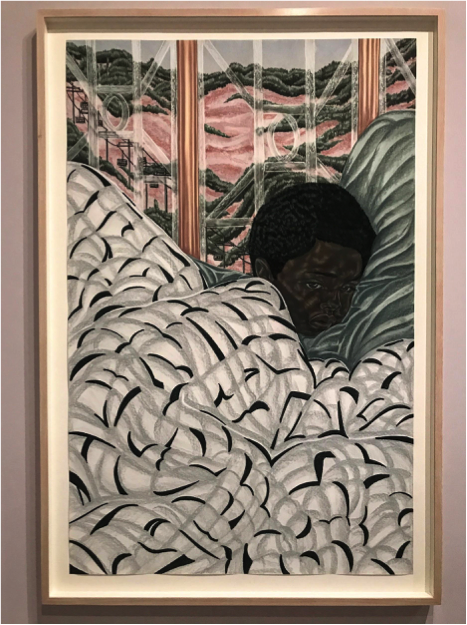

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Unfinished Commission of the Late Baroness, 2017

The delicate interplay of light and shadow enhances the ethereal quality that somehow remains much so rooted in reality. An earthly radiance and luminosity is woven into an intricate, somewhat unspoken narrative; however, while this story may be largely silent, it holds its weight through implications. Each canvas has a delicate, brushed texture – a texture that does not discriminate between foliage, object, scenery, or even skin. The material, tangible quality of the skin surface is inescapable; it is at the core of each vignette. This is a detail that Ojih Odutola clearly wishes to bring attention to, referring to the skin as this “impenetrable mark that I am expanding and making more nebulous, less static, less monolithic.” It is a concept that has been omnipresent in her work, and is clearly apparent in To Wander Determined. Here, the skin is not flat, is not lifeless, but dynamic and variable. It infuses each figure with vitality, and it enhances the luxurious quality of life that is elegantly rendered.

Both interior and exterior spaces are conveyed through delicate texture, which adds gravity to each image through visualizing the hand of the artist. “First Night at Boarding School” presents a combination of shades, though they are subtle alone. An emotive, young face cloaked in a white, flowing cloth accented with black details establishes a sense of distress existing in a separate realm. Identity is never confirmed, neither in person nor in place. In “Unfinished Commission of the Late Baroness,” identity is a topic to be questioned once again – the only bodily aspect entirely complete is the visage. She descends into sketched lines and fluctuations between light and shadow, ultimately approaching a materiality quite disparate from that which is established through the skin. Here, this materiality is more literal, no longer posed as a question or as an added weight to identity, but illustrated as a reality.

Toyin Ojih Odutola, First Night at Boarding School, 2017

Before only placing her figures in decontextualized spaces, the move into a space of narrative is a recent one for Ojih Odutola. Through narrative, she wishes to present figures in a way that evokes the sense of this has always been. There’s a degree of elusiveness that she maintains as well, keeping distance from capturing individual identity, and instead creating figures on the canvas that could be anybody, could resonate with any identity. Within this small gallery on the ground floor of the Whitney, there rests the concept of an aristocracy of a certain kind – these are figures who do not question their place, their status. They do, however, seem to question the viewer; all of the eyes give the impression of gazing past the confines of the canvas. The viewer is not necessarily being confronted, but they are not anonymous, either; they are noticed.

1 Ojih Odutola, Toyin. To Wander Determined. Oct. 20 2017 — Feb. 25 2018, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

2 Ojih Odutola, Toyin and Mary Sibande, moderated by Kellie Jones. “Art & Equity.” Barnard College, 31 January 2018, New York, NY.

Work Out: Exercise Guide for Sedentary Girls by Charlotte Barnett

1. Enter squash court.

2. Jump, using legs to push off floor. Think about dinner.

3. Jump, again, using legs to push off floor. Think about imminent death, regardless of health.

4. Fall from jump chaotically. Admit defeat to a world of photoshopped abs.

5. Think about signing up for ClassPass.

Antigone // Ismene by Elinor Hitt

Antigone and Ismene are sisters. Both speak now, at a moment when the dead must be grieved. Inspired by Sophocles’s Antigone, this is a dialogue between sisters as much as it is a dialogue with one’s own self. The scene was originally written for The Antigone Project at Columbia University.

ANTIGONE: Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles, Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes, Cicero, Vergil. Names that I know by sight. The men who built this place. I do not have a name here. Go ahead and blame me if I must be my own cornerstone, if I have no names to build on. This place was not built for me. Blame me, condemn me, if I am to be my own advocate.

Are you human if you cannot claim space for yourself? Are you human if you cannot claim your body?

You are afraid now, Creons and Haemons, that I claimed my space. That I claimed my body. You did not know that the space was rightfully yours before I took it. You feel threatened still, even after the threat of me passes. You felt most threatened when I took my own body. I am no “field to plow.” I am no progenitor. I will produce no sturdy sons, for I, myself, am not sturdy as you define sturdy. I will choose when and how I am sturdy, when and how I will be a progenitor, what I will sow and reap.

Ismene—my own flesh and blood—you couldn’t choose then, but you can now. Remember me.

ISMENE: I do not know what to choose. I do not know when silence or when voice is stronger. I know that in not knowing, things fall apart; the center cannot hold. In inaction, in silent protest, I am strong enough to endure the collapse. There is strength in silence. There is an image, an emblem in anonymity; an anonymous accusation tears down the system by way of its vagueness. Anonymity incites empathy in the least empathetic, and enrages those who cannot empathize at all.

Silence is a mirror, a reflection. Silence is moonlight, not sunlight. Silence is atmosphere. Silence is vague, the way Yeats used the word, sometime or another, cutting the page like a knife, sending meaning into decay. There is power in ambivalence. Silence is a small room that walls you in. Silence is a small room with little light. What light gets in must carefully consider where it is to fall, and must fall with precision. Patterns form on the walls and floor, making clear divisions. Silence, like light, grafts meaning onto darkness and noise.

Antigone, the reasons you became Niobe, unmoving, unflinching in the face of it, the reasons you spoke, compel me to silence. Yes, we are the same image, the same flesh and blood. But you get the privilege of death. You are respected by the law that condemns you. But I, who am honest enough to admit to a changing mind, must summon the strength to continue in the world of the living. Now, my body—which remains exposed unlike yours, which they still own—decays, dis-members, and is re-membered only into something strange and monstrous, which I do not understand. I will be allowed no graceful, westward ascent. I will not go west. But I will continue, silently, slouching onward to be born. Not a shade, but a new, strange form. Do not look back on me and see my braveness as less than yours. As a shade, can you not feel and can you not see my power brighten as yours fades?

Issue No. 1

Table of Contents

A Note from The Margin

Untitled (Pink Tear) by Alanna Reeves

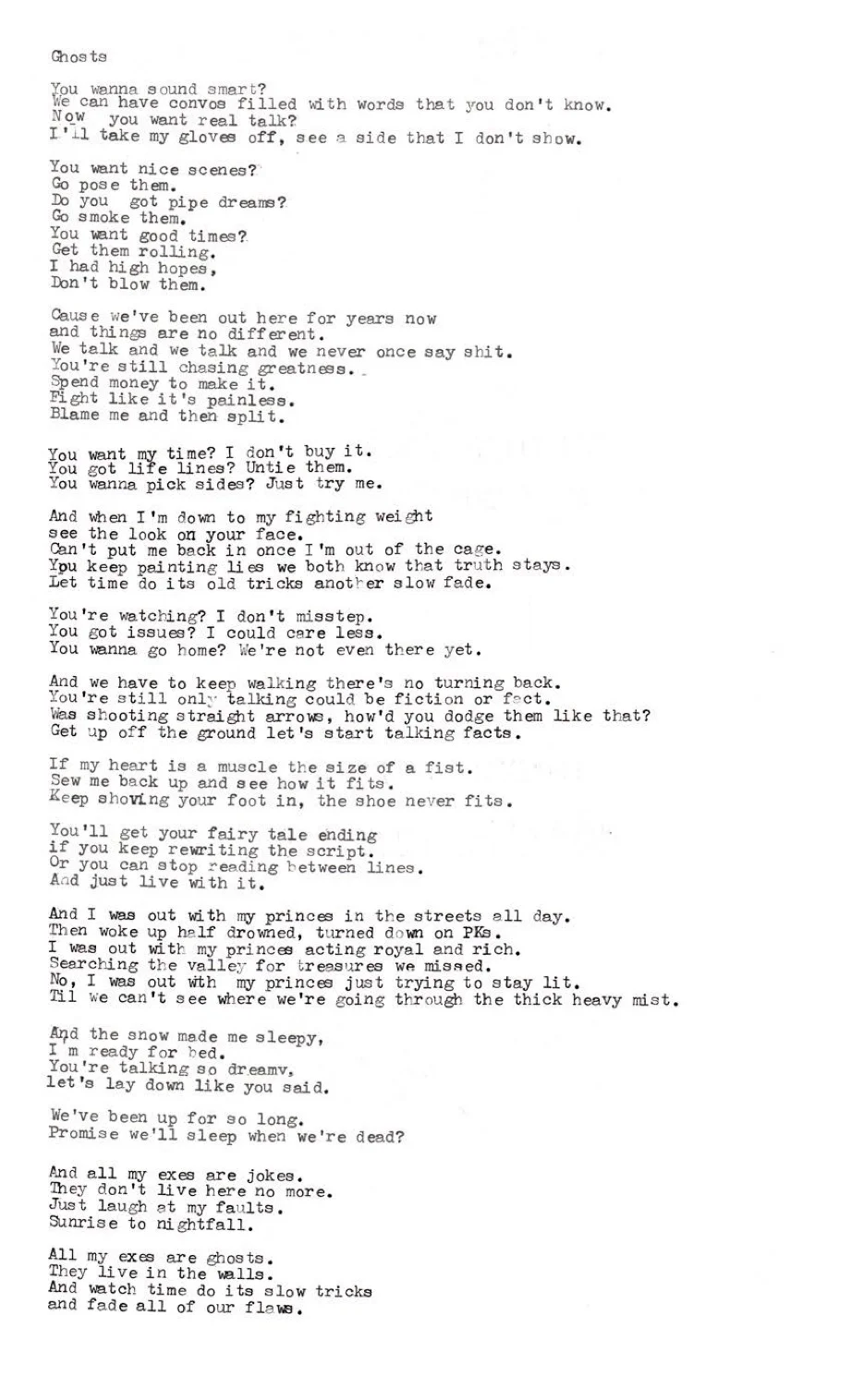

Ghosts by Gracie Bialecki

Marie Aimee Fattouche and Metro boulot dodo

On Display by Beth Miller

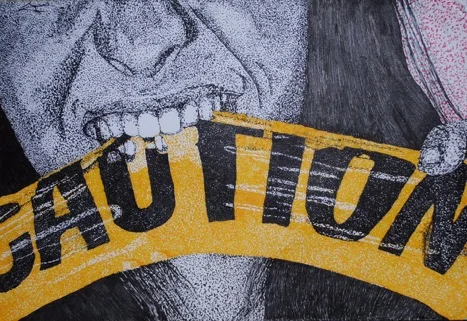

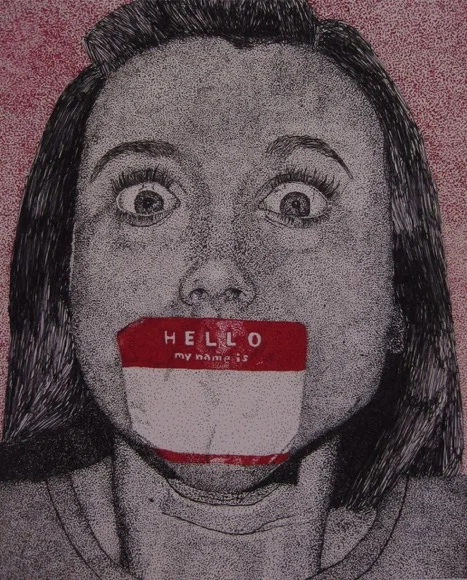

Caution and Hello, My Name Is by Shea Braumuller

Georgia O’Keeffe: Feminist by Nature by Cassidy Hall

Turning Wheel by Chelsea Hirn

From The Margin

Dear Friends,

I am pleased to share with you the inaugural issue of The Margin Magazine, a periodical journal showcasing the work of women in the arts. At The Margin, we celebrate the female voices that shape our community, and that, over the past year, have become an indispensable resource.

Our first issue features a conversation with London-based visual artist Marie Aimee Fattouche, discussing her most recent sculpture in aluminum, Metro boulot dodo, which was exhibited this August. We also have curated a series of poems, essays, and illustrations by artists from New York, Washington, D.C., and Edinburgh, Scotland. Each piece, some more literally than others, is a self-portrait. The resulting body of work is more than a collection; it is a community. Nathanial Hawthorne might recognize The Margin as a “damned mob of scribbling women,” but that mob refuses to be silenced.

On behalf of my co-founders, Charlotte Barnett and Cassidy Hall, I invite you to join the conversation! I would also like to express my gratitude to Madeleine Ohman, Marie Aimee Fattouche, and Heather Cromartie for their continued encouragement and inspiration. We hope you enjoy the first issue! Keep up with The Margin on Facebook and Instagram @themarginmagazine.

Yours in conversation,

Elinor Hitt

Editor in chief

THE MARGIN MAGAZINE

Untitled (Pink Tear) by Alanna Reeves

Ghosts by Gracie Bialecki

Marie Aimee Fattouche

Marie Aimee Fattouche is a French and Middle Eastern visual artist living and working in London. Before completing her MA in Fine Arts at Chelsea College, she worked in and around the arts, painting, designing, and curating in Paris and Marrakech. This summer, she invited The Margin to her studio, a converted industrial space situated under the railway arches of the London tube. As trains moved overhead at regular intervals, we sat down to tea among stacks of antique books. The long and narrow rooms, occupied by fellow local artists, are filled with mannequins, mirrors, props, and other oddities.

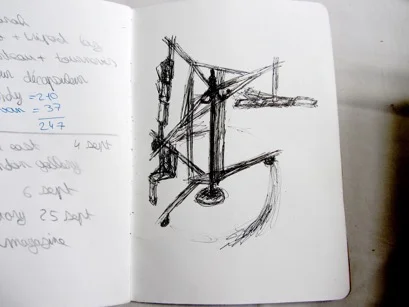

At the time, Fattouche was in the final stages of constructing her most recent work, a sculpture in aluminum titled Metro boulot dodo. The structure, with metal appendages that can be moved like a revolving door, is a statement on the rigidity and physical strain of urban life. A week later, in a group exhibition she curated, Fattouche performed with her work to exhibit a body in motion with the metal. The Margin caught up with Fattouche the day before she left for the Red Gate Residency in Beijing, China. We spoke to her about her creative process and the recent exhibition of Metro boulot dodo.

Metro boulot dodo

TM: How was the exhibition?

MA: Good vibes, good people came. I was surprised. For this show, I didn’t have many expectations and loads of people came. We dragged the party out until one in the morning!

TM: Did the audience interact with the sculpture?

MA: Some people did. I improvised a short performance. I thought I would do more movement with the sculpture, but I did it for less than an hour. I wanted to enjoy the evening. When I was showing the piece to friends, we would experiment and improvise with it.

Fattouche performs with her sculpture

TM: How did the exhibition come together? Did you organize it yourself?

MA: For this exhibition, a friend of mine with a gallery contact gave me three days in the space. I didn’t know what I wanted to do at first and I thought maybe I would do a solo exhibition. But then I realized I wanted to curate a full show so I chose the artists, myself included.

TM: Was this the first time you have curated a show?

MA: No, but it was the first time in a while. When I was working at a gallery in Morocco, I helped to curate some of the shows. It has been two years since then. It’s also very different to curate a show you are exhibiting in.

TM: The other work shapes your own.

MA: Yes, definitely. I brought a lot of diversity into the show. There was a sound piece, a performance, sculpture, installation, and painting.

TM: Can you tell us how your sculpture came to be? Can you describe what it looks like?

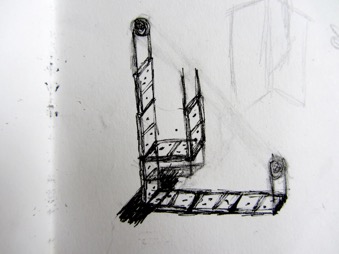

MA: My piece is called Metro boulot dodo. It’s a French expression that means “Tube work sleep.” I wanted to show the routine of urban life and what it does to our physicality. There are three positions of your body. You are not allowed to live outside of these three positions any more. You can only stand up, sit, or lay down. I thought, okay, what do I feel from this physicality? I feel quite constrained by it. Today, I have a more fluid life, as I am only focusing on my art. I feel less constrained in routine. But before, I was working in routine for six years. Your alarm goes off, you work, you go. It becomes normal to be tired. This environment made me feel like a puppet. The movement of the sculpture is like a puppet on strings—up, sit, down, up, sit, down, up, sit, down. I started drawing lines in those directions—up, sit, and down. When you write it on paper, these three signs repeated again and again look like a coded language, like Morse code.

TM: You began the sculpture by annotating movements of the body. Do you always start with sketching? How do you prepare for the first moment with your materials?

MA: All my ideas come from a concept. First, there is a lot of research, thinking, writing, and sketching. When I have an idea, I don’t necessarily know what I want it to look like. For Metro boulot dodo, I knew I wanted to work with the idea of dominoes—dominoes being analogous to humans. In the previous works I made with this idea, the pieces of the sculpture formed a strong architecture, interacting with each other socially. But in this new sculpture, I wanted to explore the form of dominoes. They are being pulled by a string and tortured by this type of movement. I start small. I start with the character of the sculpture, then I work on the context.

Early sketches of dominoes

TM: Why do you use the idea of dominoes? How do dominoes relate to humans?

MA: Many artists have worked with dominoes because they can express consequential movement. If you put them side by side and one falls, it exerts a certain amount of physical force on the whole group. The consequence, the fate interests me. I am also interested in the duality of dominoes and how they are built with differently numbered halves. My work is about understanding duality in general. Duality is not a new subject, but I try to understand it in my own life. Why do I have some moments when I am depressed and why do I have some moments when I feel very high on life? Why is there good and evil? How can they be associated?

TM: Are you going to continue to use dominoes as a theme when you go to Beijing or are you going to do something completely new? Do you know?

MA: I have no idea. Dominoes are Chinese originally. And I had no idea that I would be going to China when I started working with dominoes.

Domino details in aluminum

TM: A lot of your ideas are universal, broad concepts encompassing humanity and existence. Are you influenced by the different places you’ve lived and the different cultures you know?

MA: I guess that I am. I have never really thought about it like that. It’s true that I choose to talk about universal themes because in the end, making art is about trying to understand yourself. In any art form, the artist is trying to understand their inner-self and their surroundings.

TM: Your earlier work was about context and content. But now that you work focused on form, what you have removed is accentuated.

MA: Yes. That is the point of it. The pieces of the sculpture exist in form, but the context in which they exist has disappeared. There is deconstruction of movement in my sculpture. I realized only yesterday that I see movement by decomposing it. And I think that comes from seeing digital images. When you try to capture movement digitally, it becomes blurry. In blurriness, the content and context are lost. You can only feel the movement. I am starting to think of my work as digital. And I am starting to think about how the digital world has influenced my work. I am not very conscious of it yet. But it’s there.

On Display by Beth Miller

The muggy, sweat-filled air creates a breeze on my forearms as I move. I push through the heat—flying, soaring, turning. My feet touch the floor through my pointe shoes as I land. My chest curves backward and my head turns to the right. I see the audience sideways but only briefly.

My breath quickens. My feet cramp. My chest moves up and down, crashing each time like fast waves. My shoulders must stay in place; the audience must not know I’m tired. I must be an illusion, an image of perfection. Pretend you cannot see the sweat fly off of my forehead as I turn. Pretend you cannot hear me breathe. I press my shoulders down; I am trying to keep them still, perfect, and doll-like.

The fabric of my leotard inches down my chest. The overstretched straps cannot hold any longer. With each movement, another sliver of skin meets the hot air. Can they see my chest? How far has it slipped? I want this to be over; I want to cover myself. I am not allowed to break position to pull up my costume. They can’t know I’m human.

The music stops and I see the audience focus. I bow. I walk to the side and pull up my leotard. I am ashamed of my 15 year-old breasts and I long for the days when my body was straight all the way down. There were no curves to be seen, nothing to fall out of my tiny costume. Nothing for people to stare at with that look, as if my small leotard were not there at all.

Exposed. Naked. Vulnerable.

I am climbing up the stairs through the dark hallway of the dance studios. I hear someone behind me. I stop to look below as an older boy walks up on my right. I grip the cool handrail with my left hand. He stops next to me and looks at my shoulder from above like a hawk. He stands taller. My palm tightens around the metal railing.

His fingers reach out toward my shoulder and he spins my leotard strap around slowly, slowly. He slides his hand from my shoulder to where the strap meets the fabric, just above my chest. He lingers for a moment with his fingers hovering near my small breast.

My heart beats so viciously that I stare at my chest as my skin is pushed out and back in. My hands are shaking and my legs follow, I can’t move. His hot breath hits my ear and I want to throw up.

“There,” he finally says. “Your strap was twisted.”

His hand falls and he continues the climb up the black staircase, brushing me slightly as he passes. I sit on the step because my legs are shaking too much and I try to get my heart back into my skin.

At 16, I move into the higher level ballet class and he becomes my dance partner. I try to put that memory out of my mind. I try to pretend it wasn’t weird; he was simply fixing my strap. Dancers are supposed to be comfortable touching each other. It’s part of the job; it’s part of being a professional. And, at 16, I am expected to be a professional, although no one explains to me what that means. I only know not to cry—that’s not professional. Do not talk back—that’s not professional. Do not wear baggy clothes; slim-fitting, body-exposing dance clothes are professional. Do what you’re told without question—that’s professional. Be on time, be prepared, and do not be emotional.

Partnering class in the new level is different. Traditional pirouettes, where the boy holds your waist and you smile innocently at the audience, are gone. By now, you are expected to have mastered the classical pas de deux. Now, you must learn “mature” partnering. You must learn to use your body with another’s, not simply dancing alongside your partner, but dancing with them. You must learn to trust.

My teacher uses me to demonstrate the sequence in class.

“Use your muscles to support your body but let me manipulate you,” he tells me.

He takes one of my legs and pulls my body toward him. He wraps my leg around his hairy back, flips me, and lifts me up by my armpits. My arms are out to the side and I’m pressed up as if on a cross behind him. I’m high above the class, watching them watching me. I can see myself in the mirror, my long, slim body being lifted upward.

He tells me to bend over his shoulder and takes my waist with one hand. With the other, he takes my hair wrapped tightly in a bun and pushes my head downwards. He tells me to slide around his leg.

“No! Other leg!”

He smacks my back and I try to twist my body to the other side. “Good,” he says “and now roll onto the floor.” I slide between his legs and end the movement looking up at him. My sweaty back sticks to the cool marley floor. I look up to see the top half of my teacher’s chest obstructed by his bulging, middle-aged belly.

He looks down at me and then turns to the rest of the class. “Okay, now try with your partners.”

He focuses on the boys, teaching them how to support and move the girls’ bodies. He leaves it up to the girls to figure out their roles. Many of them come to ask me if they are doing it properly or if I could help them. I tell them that I don’t really know what I’m doing. I just tried to do what he said.

The next class, the teacher dictates the movements rather than demonstrating. He sits on his stool in the front of the room, his back leaning against the ballet barres.

“You two. In front.” He points to my partner and me.

We move to the front of the classroom and begin to decipher his combination through his thick accent and quick yelling. We try to understand the movements and remember the sequence at the same time. Meanwhile, the rest of the class attempts to follow what we are doing, watching us intently. We’ve gone through the choreography and made it to the floor, awaiting the next instruction.

“Good. Now, both of you place your hands down. Extend one leg behind you and lift yourself up, reach the other leg out into an arabesque. Closer.”

We inch closer to each other with our hands, dragging our legs behind, one foot on the floor, the other in the air.

“Good. Now kiss.”

The room is silent. The air feels hot and full. My skinny arms shake, trying to hold my body up. None of the other dancers move.

“Oh, come on! You’re going to have do this on stage someday. You need to learn that it’s not a big deal. Be professional.”

My partner leans forward and kisses me on the lips. My pink cheeks, already flushed with heat, deepen to a shade of crimson.

I have kissed a boy just once before. It happened on a swing set in the park behind my childhood house. I sat on the swing gently rocking back and forth in the autumn breeze. He leaned down. My heart picked up and my whole body felt as if it was hot and buzzing. He kissed me gently and pulled away with a warm smile.

I never imagined the next kiss would be in front of a room full of people, as I balance on my hands and one foot, wearing a small leotard.

After this, my dance partner begins to talk to me about my butt. He likes to tell me when I gain weight because he can see it getting bigger. He tells me this and I realize that he stares at my butt. I hadn’t thought about it before. Why doesn’t he focus on the choreography? When does he look at me? Can he see something I can’t?

My body expands. I watch it happen in the mirror, wondering if it’s the same thing that he sees. My breasts graduate from an A-cup to a B-cup and my partner keeps making comments about my butt. I tell him to stop but he thinks I’m joking. He says he’s just joking too. He tells me I have “a softness” about me that other ballerinas don’t.

My teachers begin to notice this too. They call me in for a meeting and tell me that I was much skinnier two years ago. What do I think happened?

I tell them it’s probably growing up, because I was fourteen then and I’m sixteen now.

“Ah, hormones,” the school director says. “Well we’d like for you to see the nutritionist and turn in food journals. You just looked much better two years ago. You know, some steps will be easier to execute if you have less around your thighs and butt.”

“Yes, and it will be much easier for the boys to lift you,” the partnering teacher says.

I tell them I will see the nutritionist, and yes, thank you for the gym membership. I’ll go there instead of doing my online high school courses. I live away from home so my parents won’t know about it.

The next time I go to visit my parents, my mom suggests that I go on birth control pills.

“It will help your cramps and your acne too. Your skin will clear up a lot. You’re 17 now and you’re about to have your own apartment. You may meet a guy soon and I’d rather you already be protected.”

I tell her that there’s no chance of that happening any time soon. She tells me that’s precisely when you meet someone: when you don’t expect it.

A few months after this, I meet a guy—another dancer. He takes my virginity and tells me I have a big butt for a ballerina.

Caution Tape and Hello, My Name is by Shea Braumuller

Georgia O’Keeffe: Feminist by Nature by Cassidy Hall

Last June, I journeyed from my Harlem apartment to the Brooklyn Museum for the greatly anticipated exhibition Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern. In the winding galleries, I not only found the unapologetic feminist art I had come to see, but also an earnest portrayal of the human experience; I learned from her strength and from her surprising sensitivity. Georgia O’Keeffe, a woman who transformed American modern art, challenged gender norms, and quite literally wore her pride on her sleeve, changed how I define feminism.

The simplicity of O’Keeffe’s paintings is striking. Each of her pieces makes a subtle statement. A flower, no matter how grand, is still a flower. Many audiences, including her late husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, claimed her flowers are comparable to female genitalia, metaphors for blossoming sexuality, or overwrought feminist statements. O’Keeffe rejected these observations, retorting that viewers only see what they want to see out of art: “you hung all your associations with flowers on my flower… as if I think and see what you think and see—and I don't.” Rather, O’Keeffe was drawn to flowers for their common beauty. She sought to eliminate any distractions from the subject of her paintings, emphasizing instead simplicity and form.

The minimalism of canvases covered entirely by singular, bold blossoms is translated into her later work, especially her paintings of skyscrapers. O’Keeffe’s illustrations of New York are not as busy or as crowded as many of her predecessors’ portrayals of the city. Instead, she intensifies the nobility of the craning buildings. Staying true to her fondness of striking color and clearly defined shapes, O’Keeffe eliminates all excess from the cityscapes, allowing the architecture to be the centerpiece. Seeing city life portrayed in such a raw form, I was overcome by hope and loneliness. My insecurities were drawn to the surface by the authenticity and simplicity of the statement. Beholding nothing but the angular, monochromatic skyscrapers, one begins to impose one’s own experiences onto the artwork. Perhaps this is why so many critics pass judgments about the underlying meaning of O’Keeffe’s statements: O’Keeffe begs her audience to realize their personal emotions in art.

The most poignant display in the exhibition was a series of photographs of O’Keeffe. The portraits demonstrate that O’Keeffe’s art is inseparable from her character. She often stands like a western cowboy, ruthless and present, demanding the camera to capture the angles of her body: the sharp incline of her chin, the daring expression of her eyes, and her strong, yet graceful disposition. Her taste in fashion is a reflection of her demanding presence. She plays with gender neutrality in clothing, sourcing inspiration from her environment. Whether wearing button-up blouses, cowboy hats, or trench coats, O’Keeffe presented herself with tactful, consistent care. She gravitated towards clothes that reflected her artwork: three white blouses hung proudly and delicately in a row at the museum, curated to mirror her paintings of flowers. With no attachment to either gender, the androgynous wardrobe bears a neutral and unassuming beauty.

Much like her paintings, O'Keeffe’s style is inspired by her environment and its natural resources. She immersed herself in her surroundings and like a hawk circling the western prairies never went unnoticed. In New Mexico, O’Keeffe redefined herself, fusing her art, habitat, style, and character into one identity. Contrasting to her nostalgic cityscapes, O’Keeffe’s renderings of the American southwest exude majesty and incite curiosity. Amid joy and color, O’Keeffe paints skulls, carcasses, and empty space. The contrast functions as a memento mori, expressing human suffering and existential doubt in physical form. She creates an intricately shaded world where life and death are equals, gender is as fluid as changing outfits, and flowers and skyscrapers alike are iconic. Embodying her aesthetic philosophies in both her art and identity, O’Keeffe was not a feminist by choice but a feminist by nature. Her art is influential not only because it serves to empower women, but also because it exposes the universal need for free self-expression. Indeed, O’Keeffe’s legacy is proof that feminism is innate in all of us.

Turning Wheel by Chelsea Hirn

In my mind, I see a woman as sturdy as the tree she sits under.

She does not flinch when the growing wind touches her face, nor when

The tide of grief wants to pull her under.

She simply sits, bones like roots, no reaction as the breeze

Tosses deep red curls around her face

And deep red leaves around her body.

She just is, like the tree, knowing fully

That this is a season of her life, and like any other,

It will turn on the wheel,

It will grow heavy, shed, and bleed

And then grow full again, and again.

She did not feel despair when her hand mirror

Began to show wrinkles where freckles had been,

Though perhaps she let fall a tear or two.

She did not have to mourn long the passing of the freedom of her youth

Because every moment was spent

In good company: her own,

That of her heart.

And she always knew this day would come,

And lived her youth in greater abandon and relish

Accordingly:

She burnt it wild, like fire.

She will not cry out when her scrying mirror

Begins to show her days slowing down,

Red turning to amber, and then silver.

She knew from her first morning under this tree,

When her cheeks still glowed pink

And her bones were little more than sprouts,

That not one of her days would be alike to the last, nor the next.

She found freedom there.

In this moment, she knows that

Though this growing storm,

Kindled by the glorious sweep of her unbridled impulse,

Will blaze around her, grow hotter, wetter,

Soak her dress,

Tangle her hair,

Turn the earth beneath her to mud,

Pull her down, deeper, to rot among autumn leaves

She knows that rot is creation,

That rot becomes soil, and soil trees.

She knows that

Though the fires she lit behind her through her living

Have caught up to her, and she has much to answer for,

Fire clears the soul,

Like the woods,

Of old and gnarled things begging to end,

Makes ready space for seeds.

I see this woman in my mind,

And I try to hold fast to her,

But each of my days is a season unto itself,

Each bringing a dozen storms

And a hundred new leaves,

And her image fades,

And then grows,

And fades again,

And I do not know her freedom, or her strength.